It was disappointing news. The results of his physical read “4-F, unfit for military service” due to a nagging knee injury that still plagued him years after he damaged it playing sandlot football. The year was 1967 and the military was drafting 50,000 men per month. War raged in Vietnam and the U.S. Army had just violated an unwritten rule of engagement: they told Steve Stanaway he wasn’t good enough. Three days later, Stanaway decided to enter the Most Physically Fit Man in Virginia contest and not only did he win, he dominated, taking first place in four of the seven events. He showed them.

Such stories about Stanaway seem too many to mention. There was the time another armwrestler challenged him and Stanaway brought him a gift-wrapped pin-pad. Then there was that time when he read a newspaper during a match, while holding an opponent who said Stanaway would not beat him if not for his blazing fast speed on the table. Or that time he wore a US Navy shirt with a veiled nuclear threat on it to a predominantly Muslim country for the world championships shortly after 9/11. Such is the story of Steve Stanaway. While he might not be looking for a fight, he is not exactly shying away from one. You can be certain of one thing: Stanaway is going to let you know where he stands and where he goes, controversy usually follows.

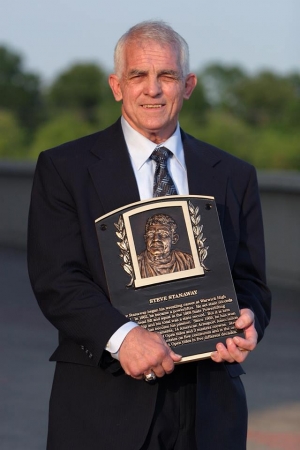

This photo is courtesy of the City of Hampton, VA. Steve Stanaway holding his Athletic Hall of Fame Plaque

Though his muscles have atrophied some and his skin now wears the weather of nearly 300 seasons, Stanaway fights age much in the way he has faced other seemingly insurmountable opponents: with brutality. Like General George S. Patton before him, Stanaway has been criticized for using questionable tactics during his career as a referee and vicious competitor and yet has left an indelible mark as a pioneer, a game changer and the history of armwrestling has no choice but to remember him a winner.

Stanaway, 72, has been as certain a part of the sport of armwrestling as a table and chalk and as sure as a petrichor scent after a hot Virginia summer’s rain. Despite the onset of arthritis, his hands are still capable of crushing what and who they grab. Despite decades of battle on an off the table with competitors and promoters alike, there remains a hard edge, a saltiness, partly from more than 43 years as a pipefitter in the unforgiving sea air of the shipyards in Newport News, VA and partly because of a chip that seems permanently affixed to his shoulder.

The only thing possibly stronger than his arms are his opinions and his defiance has garnered both applause and opprobrium. Despite the uncompromising edge, Stanaway’s sentiments are only so unwavering because of one simple fact: he cares. This is perhaps what separates him from the younger man who only competes to prove self-worth. More things matter to Stanaway. The advancement of the sport of armwrestling matters. Preserving the history of the sport prior to this modern digital age, matters.

But there is more to it. It isn’t just about a sport. It is about morality, with Stanaway. It is about fair play in life and on the table. It is about hard work. It is about seeing value in nearly all virtues, except possibly forgiveness. When asked if he could ever forgive and forget, Stanaway immediately answered in a very Pattonesque way, “never.” Patton had his ivory-handled revolvers, which spoke to the flamboyance of the man. The only guns Stanaway ever needed were attached to his shoulders. If there is one element of Stanaway that depicts a more human side, it is his friendship with his dog, Reagan. Dogs don’t do betrayal and rarely do they disagree. It is also why the perception of abandonment stings him so much. It is because loyalty and friendship matter. It is because relationships matter. What seems to matter most to Stanaway is being right. This can be the roadmap for a lonelier life as men of principle often have impossibly high standards.

It is also, however, where the passion comes from; it is why in every conversation with Stanaway, one can still find a competition. It’s why he has such a penchant for remembering incidents and dates. While such intensity can often be exhausting, it is what keeps the youth in his heart and maintains the acuity of his mind. An armwrestler who preferred not to be named once said of Stanaway after he was fouled out by the aging, grizzled ref, “he is too damn mean, too damn tough and too damn stubborn to die.”

This competitive nature was instilled in Stanaway growing up as the second oldest of nine children in a modest Virginia home with a father who was “a hard man,” according to Stanaway. “He was hardest on me,” Stanaway said. “I was the athlete of the family and I had an attitude. Maybe that’s why I am the way I am today.” Stanaway was always willing to push back and he was always larger than his size indicated. Though too small physically to compete at a high level in football, he found his home as a wrestler, making it to the Virginia state championships out of Warwick High School in Newport News in the 147 pound weight class. Where he really excelled was in the areas of lifting weights and physical fitness. When Stanaway found weightlifting in 1962, it stuck with him like his tidewater accent.

He also enjoyed to armwrestle because he loved the one-on-one competition. “It’s pure competition,” he said. “You win or you lose; you have no one to blame.” In 1966 he gripped up with his first formidable opponent, a man named Bob Jones. It was a pre-arranged matchup in a Burger King parking lot where the two agreed to armwrestle for money on the hood of a car. At the time, there was a local hustler known as “Finance” who arranged and funded such underground events, bringing out locals to gamble on their favorites. “Finance looked for talent,” he said. “If you could shoot hoops, play pool, armwrestle and you were good, he would line up matches.” Stanaway ended up winning. Little did he know at the time this would start a trend that would continue for more than 50 years.

In 1967 he was tapped to do a strength show with the legendary Paul Anderson at MacGruder Elementary School in Hampton, VA. On that day, Stanaway, a starry-eyed, 23-year-old performed a triceps dip with 300 pounds attached to a belt from his waist in front of one of the iron game’s greatest legends and Anderson would successfully execute one of his celebrated 1000-pound-squats in front of Stanaway and the local crowd. Anderson, who passed away in 1994, was almost universally regarded as the strongest man in the world at that time, an Olympic gold medalist and a man who played an integral role in popularizing power-lifting as a sport. “I am one of the few people left who can say they did a show with Paul Anderson,” he said, proudly.

Stanaway said he always enjoyed doing curls and dips above all other exercises and had performed dips with as much as 315 pounds added to him. Legend has it that Stanaway bench pressed 400 pounds the first time he ever tried. In 1968, Stanaway competed in the fourth annual Virginia State Powerlifting Championship, which took place at the Cavalier Hotel in Virginia Beach, VA. At that time he had only been bench pressing three or four months and competed in the 198 pound class. That day, he set the state bench press (460 pounds), squat (450 pounds), deadlift (550 pounds) and total records (1,460 pounds). “This was raw,” he said. “Back before the drugs and the bench shirts.”

Though his best bench was 475 pounds, Stanaway said he regrets not hitting the 500 pound mark prior to discontinuing his focus on bench press and finding his true labor of love, armwrestling. “Armwrestling and powerlifting do not mix,” he said emphatically. “I had a choice: quit armwrestling or quit powerlifting. I decided to quit powerlifting because I had a bum knee and could not keep up with the guys doing heavy squats.” Around the same time, Stanaway said he also stopped focusing on heavy dips. “I had to quit the dips because it was tearing my damn hemorrhoids up,” he said with a chuckle. The late strength historian, Merle Meeter often acknowledged Stanaway’s famed 210-pound-hammercurls and 330-pound-wrist-curl feats, which would still be considered world-class today.

September of ’68 also marked Stanaway’s initial foray into organized armwrestling when he made it to the semifinals of the “Show of Shows” event at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in New York, sanctioned by the International Federation of Bodybuilding. Stanaway ended up losing to John Torch in the semifinals and Torch lost in the final to the legendary Maurice “Moe” Baker from Connecticut. Following the contest, Stanaway was hooked. This event also marked the first time he met Bob O’Leary, who with the help of Stanaway, would develop two of the most successful organizations in the history of the sport.

In 1969, Stanaway won enough money in an underground match, once again arranged by “Finance,” to fund his travel to the World Wristwrestling Championships in Petaluma, CA. He armwrestled a man whose name he could not remember at the Thirsty Camel in Norfolk, VA for $1200, competing both right and left-handed. “You have to think about the time,” Stanway said. “That was a lot of money back then.” According to Stanaway, one of the onlookers said to his opponent “Don’t worry, Jesus loves you,” to which Stanaway replied “He better.” Stanaway ended up beating the man and earning more than enough to pay his fare to Petaluma in 1970 where he took second place to Jim Pollock, a perennial champion at Petaluma. “He was the only person I never beat,” Stanaway said of Pollock. “I never got another shot at him.”

Photo courtesy of New York Armwrestling Association

Stanaway also began a new role in the sport of armwrestling. As a promoter, Stanaway is credited as being one of three Americans who worked tirelessly in the development of the Word Arm-Wrestling Federation (WAWF) with O’Leary and the late Ed Jubinville, an organization which would later become the WAF. O’Leary established the organization in Scranton, PA in 1967, holding events at the local YMCA. Stanaway recalled a need for more organization because at the time, armwrestlers attended events based on written notifications they received and would often, to their chagrin, show-up to find empty venues.

In one of O’Leary’s events held at the YMCA in Scranton, PA in 1969, Stanaway won the under-200-pound weight class. This started a trend as Stanaway would win major events in each of the following decades up until the present day. The 1970s was Stanaway’s heyday. By 1975, Stanaway would be recognized as the first man to reach 100 armwrestling titles at an event in Louisville, KY. Among those titles were seven Atlantic Coast Championships as Stanaway took first place at 200 pounds every year from 1972-1978. In 1975, his brother Randy Stanaway joined him competing in armwrestling.

Randy indicated that he did not train with his older brother Steve because he was not a part of his training group and said being left out certainly motivated him to become a champion in his own right. To this day, Randy still reveres his brother for his accomplishments. “He was just so doggone strong,” said Randy, himself known for having incredible endurance. “Two things I can say about Steve as an armwrestler was that he was the strongest natural man I have ever seen, pound-for-pound and the guys around today would be in for a real eye-opener if they could have armwrestled him back then.” Randy, 58, indicated that his older brother’s appearances on ABC’s Wide World of Sports made him a local celebrity. “I have never been jealous of anybody even though I was always in his shadow,” Randy said. “People everywhere around here just knew who he was. Still today people will come into my business and ask about Steve.”

Stanaway was having similar success internationally as well attending the Carling O’Keefe World Championships in Timmons, Ontario in the late 70s. According to Stanaway, the only time he lost was the year the airline misplaced his custom made armwrestling shoes, with a platform heel. “In 1977 I went to Timmons and I won,” he said. “In ‘78, the damn airline lost my shoes and I got beat. ‘79, I went back to Timmons and carried the shoes with me and I won,” he added with a grin.

He did mention that Al Turner ended up winning the event in 1978. “1979 was supposed to break the tie between me and Turner,” Stanaway said. If Turner was armwrestling’s version of Babe Ruth, Stanaway has been more of the sport’s Ty Cobb. In their eight battles, Stanaway and Turner each claimed four wins and Stanaway still refers to Turner as “probably the greatest armwrestler of all time.” He said he had a chance to have a rubber match with Turner in the ‘79 O’Keefe Worlds but they never met. Turner lost a long match to Reno’s Bob Howell in the semifinals and Stanaway eventually won the tournament over Howell.

At the same time, Stanaway was promoting events as the American Armsport Association’s (AAA) Virginia state director, a position Stanaway held from 1970-1981. 1978 was a critical year for armwrestling as the “two-minute time limit” rule was abolished, which decided a winner of a match after the time-clock ran out regardless of whether or not one of the armwrestlers were pinned. If one armwrestler was in a winning position at the end of the clock, they were declared the winner. “That didn’t bother me because my matches were over quickly,” he said. “But enough people disliked the rule to do away with it.” It was also the final year the Scranton YMCA would play host to the world championships.

The following year John Miazdzyk would host the first world event held outside of the U.S. in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada with just four member nations, the US, Canada, Brazil and India under another of the sport’s pioneers, Barij Baran Das. Shortly thereafter, Bangladesh, Italy, Mexico, Guatemala, and England would come calling. In the years to come the two-foul rule was instituted, remembers Stanaway, allowing competitors a second foul to prevent matches from ending without pins. As the sport saw growth and progress in ’79, Stanaway was busy being honored as the AAA Armwrestler of the Year. During the 1980s, left-handed and masters divisions were also added to the docket and by 1996, the world championships were attended by competitors from 70 countries spanning six different continents. Even Stanaway’s most ardent critics cannot deny the role he played in such growth.

In January of 1980, while recovering from a surgery on his elbow, Stanaway took on a new and possibly his most controversial role in the sport. He began working as a referee and would later become the AAA and WAF head referee for 24 years. As a referee, Stanaway has drawn comparisons to Dirty Harry because he did not discriminate and it seemed at times as though he hated everyone. This approach drew the ire of competitors who have accused Stanaway of everything from favoritism to racism, accusations he vehemently denies. To Stanaway’s credit, he was always willing to throw out any competitor from an event who stepped out of line, even his own brother, Randy on one occasion. The kicker: their parents were in attendance at that specific event. “I caught hell from my mother and father,” he quipped. Randy called him “a cheatin bastard,” though chuckled afterward. “I always thought Steve was a good referee but I would get the short end of the stick on some calls because he didn’t want to show favoritism.”

Stanaway was also willing to give a young lady a chance to become a referee, something unheard of and surprisingly progressive in the sport of armwrestling at that time as many other officials were against it. Karen Bean, the current co-owner and promoter of the AAA indicated that it was Stanaway who enabled her to referee major events after she spent 12 years as a competitor. “My arm was completely shot,” Bean said. Stanaway had allowed her to test as referee for national and world competition. “In the process, he caught hell from some of the other officials,” Bean added. She said Stanaway treated her like another one of the guys. “I was granted no privileges whatsoever due to our friendship. As a result I was the first woman to ever stand on a stage at a national or world event as a referee. I owe Steve a debt I absolutely cannot pay.”

As a promoter and organizer, not only had he helped develop a worldwide organization as well as the AAA with O’Leary, he cohosted the National Championships in Williamsburg, VA in 1979, Newport News, VA in 1982 and Farifax, VA in 1984 and again in 1989. He would later cohost the WAF World Championships in Virginia Beach in 1996 with his brother Randy and again in 2000 Randy as well as Frank and Karen Bean. “I never saw someone more dedicated than he was,” his brother Randy said.

Steve's championship jackets. Photo by Noah Retarides

In 1986, Stanaway was one of only a few unafraid to voice their criticism of the Over The Top series of events, which culminated in the movie featuring Sylvester Stallone. Stanaway was a referee at one of the qualifying events in New York where he ejected Rick Zumwalt for unsportsmanlike behavior, after Zumwalt reportedly insulted referees and kicked the scorer’s table repeatedly. The tournament’s director allowed Zumwalt back into the competition and he later earned the supporting role in the film as antagonist, “Bull Hurley.”

While Stanaway had benefitted as a head referee of the events in the U.S. and Europe, which qualified armwrestlers for the finals in Las Vegas, he criticized the promoter for his management of the finals in Las Vegas where Stanaway felt like the event was “staffed with several unqualified referees” and believed “some bias was shown.” He felt he needed to speak up for the competitors who traveled to the event because, in his words, “they were not shown respect.” Stanaway walked off the stage and out of the event. As often was the case, he took an unpopular stance because he believed he was right. “Steve is fierce in his support and protection of the sport he dearly loves,” Bean said. “He’s seen many self-serving, greedy individuals come and go through the years that dared to call themselves promoters. These ‘promoters’ found themselves fiercely hated by him and he didn’t think twice of letting them know it.”

Though Stanaway would be inducted into the WAF Hall of Fame in 1987, it was not until 1996 that Stanaway would receive what was perhaps armwrestling’s greatest honor, “The John Miazdzyk Award.” It is no mistake that on this award the words “dedication,” “leadership,” and “loyalty” are inscribed. “(Stanaway’s) accomplishments in this sport are second-to-none,” Bean said. “He was a fierce competitor, rarely losing. He most likely could be called the fastest man in armwrestling. Most referees could never even move their hands an inch to two inches out of the center of the table before Steve had his opponents pinned.” Stanaway would continue to serve on the Board of Directors with the AAA until the board was dissolved in 2000. Four years later, Stanaway was endowed with the AAA Lifetime Achievement Award. Through much of this time, Stanaway would serve a very important role at the premier event of armwrestling of the late 90s and early 00s.

After meeting event organizer Fairfax Hackley and working alongside him as a referee at a tournament in Scranton, PA, Stanaway was asked by Hackley and O’Leary to become the first head referee of the Arnold Schwarzenegger Classic, a position he held until the AAA and the event organizers severed ties in 2003. It was Stanaway’s loyalty to the AAA that kept him from continuing to ref at the Arnold Classic. Despite the differences of opinion with AAA, Hackley indicated that he wanted to retain the services of Stanaway as referee. However, there was a rule at the time that said he could not referee with other organizations, so Stanaway declined. In hindsight, he indicated he would have continued refereeing the event if he could make the decision over again.

One thing he continued to do: armwrestle, winning masters’ world titles in 2003 and being recognized for his achievements in his home state of Virginia. The Peninsula Sports Club honored Stanaway for the Sports Person of the Year in ‘03. Among the people he beat out for the award was Michael Vick, who also hails from the lower peninsula of Virginia. As it turns out, Stanaway’s animosity for Vick would be magnified following Vick’s arrest due to dog-fighting allegations. “I can’t stand Vick, that son of a gun,” Stanaway said, choking back some tears. “I went to all three of his trials.”

Stanaway spoke a bit about the horrific things he heard during those trials and admonished his coworkers at the shipyards at that time. “They think he walks on water in that part of the state,” he said of his coworkers’ sentiments of Vick. Following the trial, Stanaway brought his dog “Dinky” to the shipyard. One coworker, trying to get a rise out of Stanaway said “I am going to put a hit out on your dog.” To which Stanaway said “something happens to my dog I ain’t comin for nobody else but you.” Stanaway would be reprimanded for the threat, despite the fact that he was so close to retirement. Though like many such moments, he certainly doesn’t regret it.

Stanaway chuckled at accusations that he would give fellow Virginian Dave Patton preferential treatment at the Yukon Jack events of the 1990s, specifically when armwrestling Allen Fisher. “I always liked Fisher,” Stanaway said. “I caught up with him in Vegas last year and spoke with him. He and I are fine.” Fisher shares equal reverence for Stanaway. “Steve has stayed the course of the history of armwrestling,” Fisher said. “He gave of his time, money and talents supporting armwrestling for decades and his name will be remembered longer than his years he dedicated to the sport,”

Most competitors would describe Stanaway as perhaps too firm as a referee but rarely biased. And yet allegations of bias would precede Stanaway’s resignation as head referee for AAA in 2005 after a similar inference that he would show favoritism to one of his teammates at an event. Stanaway indicated that he agreed to sit out and allow someone else to referee ahead of time to avoid such accusation. When the accusation came anyway, Stanaway was furious and stormed out of the event onto the famed Atlantic City boardwalk. “It wasn’t just one situation,” he said. “The ice had been cracking for a few years,” he added regarding his relationship with the AAA.

Team Brutal: photo courtesy of Jean Okyen

Though 2005 would be the end of an era for Stanaway, it was also the year he was inducted into the Athletic Hall of Fame of the Lower Virginia Peninsula, where a plaque and bust of his shoulders and face are featured. The National Armwrestling League would later give Stanaway its lifetime achievement award in 2013 and in July of 2016, the Professional Armwrestling League would follow suit at an event near Scranton, Pennsylvania, the city where his winning began 47 years prior. Stanaway is credited with winning more than 200 tournaments including 32 combined world and national titles in a career that is still semi-active. Stanaway still invites one-on-one challenge matches but they have to be in armwrestling straps due to his arthritis, he indicated.

As an armwrestler in today’s strength-sports climate, Stanaway does give credit where it is due to newer athletes but of course levies some criticism. As a legend of the golden era of armwrestling, Stanaway has disapproved of the modern armwrestler’s propensity to use excuses, specifically when it comes to their avoidance of sit-down armwrestling, which he and his brother Randy promote. “Everybody has an excuse and everybody’s excuse is legit,” he said sarcastically. “After talking to forty-to-fifty people about why they won’t armwrestle sitting down I have come to the conclusion that it has to be 72 degrees, a gentle breeze blowing five miles per hour from the south, zero humidity and clear blue skies in order for them to compete.”

Steve believes the modern focus solely on stand-up armwrestling prevents us from really knowing who the best armwrestlers are and said placing third in the old days at both sit-down and stand-up national events was what brought you respect among the armwrestlers. To win both, he said, “you had to be brutal.” And Stanaway was just that, as “Brutal” was the moniker he earned not only as a competitor but a frequently embattled referee. He was known as a brutal prankster, could be brutal to his opponents and as always, is brutally honest, even with himself. When asked about the vanity plate that reads “Brutal” on the front of his Ford F-150, he quipped “The guys tell me I should change it to read: ‘Brittle.’ Probably so,” he added with a laugh.

Stanaway pointed out that the armwrestlers of yesteryear would frequently compete in either style. “We would be in Pennsylvania pulling stand-up one week and two weeks later pull a sit-down event in Georgia,” he said. “Today’s armwrestler can’t do that. When we armwrestled back in the 60s and 70s we armwrestled on the hood of a car, bars, picnic tables, kitchen tables, a 55-gallon-drum. Anywhere there was a surface for both people, we armwrestled on it.”

Stanaway is particularly critical of the steroid culture. He said he couldn’t laud the modern champion who is “only really half of what he is.” Stanaway has been outspoken over the decades against the use of performance enhancing drugs because he said fairness in competition is so important to him. “I saw the sport start drifting toward drug use during the mid-80s,” Stanaway said. He referred to steroids as “the ego drug,” and was highly critical of competitors who use and then attempt to give nutritional advice to others. “They are doing nothing but misleading people,” he said.

Stanaway indicated that he was always a competitor but never considered himself a sore loser. “It is important to know how to lose,” he said. “If you can’t afford to lose, don’t go up to that table. I didn’t want Al Turner to beat me, but he did. I didn’t want Moe Baker to beat me but he did. I didn’t like it but I just went home and trained harder.” Stanaway pointed out that a major difference today is that athletes have an abundance of video clips to review. “There was no video to study back then so I learned a lot of my armwrestling by refereeing,” he said. “As a referee, you can watch the best armwrestlers and see how they approach a match, where they place their hand and elbow and what pressure they give before the start of the match. You learn different styles.”

Stanaway is no longer on speaking terms with the majority of the older promoters and practices avoidance whenever possible when it comes to the subjects of his feuds because as he says “it is not what you say to someone, it is how they receive it.” Stanaway demonstrated concern not only for how others will interpret his words but how he would receive theirs as well. In that way he does not always trust how he will react to people. “I don’t chase people down, now” he said. “I just try to walk away.”

Bean admitted there were several times during their friendship of more than 40 years that her and Stanaway went without speaking. “We’ve been as close as any brother and sister could possibly be,” she said. “We’ve fought, argued and disagreed, yet still love each other.” Bean indicated that they have spent years at a time without contact, something she attributed to both of their “hard-headedness,” but said they would often rekindle a friendship where they could confide in each other. “I have stood toe-to-toe with him many times wanting to strangle him due to his actions but at the same time will defend him to anyone,” Bean said. “Steve can be as hard-headed as they come and then two seconds later be as kind as can be. He will argue principles with his last dying breath. He’s a man who publicly refuses to apologize to anyone but yet if he cares about you, he will let you know he is sorry if he has upset or hurt you.” Bean referred to Stanaway as an “anomaly” in the present culture. “He will tell you exactly what he thinks, pull no punches, mince no words,” she said. “Yes, he is rough, no question, but if you know him, you will always know exactly where you stand with him. He sugar-coats nothing and answers to no one.”

As with many such men, this resolute approach has been evident in Stanaway’s personal life. Stanaway talked about how some of the football players he went to school with bullied him and some of the smaller guys, making them bus their lunch trays from the cafeteria. Decades later he wanted to go to his class reunion to “say something smart to them in front of their wives, girlfriends, moms, dads or kids.” His wife at the time said she would not go if Stanaway insisted on being confrontational. “So I never went,” he said.

Stanaway is divorced and now lives alone. He acknowledged seeing his ex-wife after his divorce when he was in a local Wal-Mart picking up some miscellaneous items prior to traveling for the World Championships in Tokyo in 2005. Stanaway said she approached him to say “hello” and asked how he was doing. He walked away from her and realized shortly thereafter talking to fellow referee and old friend Mike Bonelli, that “she won.” This, he said, was due to the fact that she was able to let go of their differences and talk. Stanaway was not. And yet the interesting dichotomy is that he is the type of person who would do anything for a friend regardless of this competitive script which has spilled over into even the most personal of his relationships. “If you needed him, he was right there for you,” his brother Randy said. “If you were right, he would stand up for you. If you were wrong, he would let you know it.”

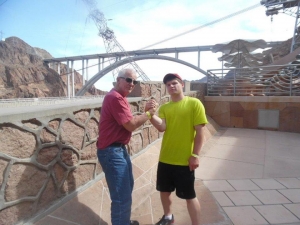

Steve Stanaway and Chris Okyen. Photo courtesy of Jean Okyen

When you think you have a man like Stanaway figured out, he surprises you. Jean Okyen met Stanaway at an armwrestling tournament in 2014 after witnessing what some might believe to be an unconventional sight. “I remember Steve holding his little dog Dinky on his lap,” she said. “I found out later that Dinky was very sick and Steve did not want to leave him alone so he carried him around the whole day.” Stanaway would befriend Okyen’s son Chris at that event and became a mentor and coach for Chris, who has Asperger’s, a high-functioning form of autism. “Steve opened up a whole new world to Chris,” Okyen said. “They have trained together and traveled to many cities to tournaments and have met many great people.”

Okyen believes this friendship has been equally rewarding to both parties. “I think mentoring Chris has renewed Steve’s love for the sport of armwrestling,” she said. “In fact, Steve seems younger today than on the day we met him.” It is interesting to observe the two as Stanaway demonstrates a greater level of patience and understanding for Chris. When asked if Stanaway was becoming more tempered in his age, his brother Randy said “Steve is getting to a point in life where he is afraid to be alone.”

When asked what having a friend in Stanaway has meant to him, Chris Okyen said being around him was “like being around living history.” Okyen referred to Stanaway as more life coach than armwrestling coach. “He is the most loyal friend you will ever know,” Okyen said. “He took me under his wings, allowed me to get out and interact with people and be more social.”

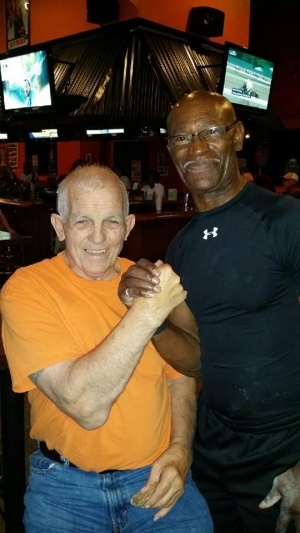

Steve Stanaway and fellow former world champion Milt Christmas

Steve Stanaway is a complicated man. He can be affable, generous and understanding, yet terse, vindictive and unforgiving. One thing which cannot be argued is that when he does something, anything, everything, he means business. To Stanaway, life is a competition and he has only one focus: winning. Winston Churchill once implied that having enemies is indicative of a man who has stood for something. Stanaway has embodied this as a pioneer in the sport of armwrestling and so justifies his efforts. “I had a politician once tell me that if you are in a position of authority and you are not stepping on someone’s toes, you are not doing your job,” he said. “You cannot make a change or make a difference and please everybody.” Ironically, Gandhi believed holding grudges was a sign of weakness and called forgiveness “an attribute of the strong.” Like in Greek tragedies, hubris may be his Achilles heel. And yet Stanaway would certainly be deemed heroic in a modern sports culture that tends to value revenge and dismiss forgiveness.

In plays and movies, riding off into the sunset if oft romanticized but in interviewing Stanaway, one gets the impression that he will have to be dragged off stage. In October of 2014, Stanaway had some shortness of breath. He indicated that he had a heart rate of 150 beats per minute and doctors could not find a way to normalize it for five days. He was diagnosed with atrial fibrillation, and had to be shocked back into sinus rhythm. And yet he has no plans to slow down as Stanaway plans on competing in 2018, which will make him the first armwrestler to compete for more than 50 years and if he competes in 2020 he will be the first to compete in seven different decades. Though it has been a tumultuous love affair, the sport of armwrestling brought Stanaway to five continents, 22 countries and nearly every state. “Armwrestling brought me to a lot of places and helped me build self-confidence,” he said. “A lot of people have low self-esteem but let them excel at competition and watch what happens. It changes their life.”

James Retarides